makes national magazine's "Best of Adventure List"

December 2005

By Lisa Brainard

Bluff Country Reader

Iconoclast. That’s a word sure to send people scurrying for their dictionaries.

It’s also a word used to lure readers into the December 2005/January 2006

“Best of” issue of National Geographic Adventure (NGA) magazine. It lists

the top 10 adventurers of 2005, splitting them into the categories of

“Elites” and “Iconoclasts.”

You’ll find Fillmore County caver and Cave Preserve owner John Ackerman

in the latter.

“What’s an ‘iconoclast’?” Ackerman asked.

He was initially contacted by writer Geoffrey Norman in September. Norman

told him it was someone who doesn’t follow the norm. For example, a person

climbing big rock walls without the security of ropes. He also noted they

were looking the “best of the best.”

The author apparently found out about Ackerman’s passion for caves by

talking with members of the National Speleological Society. He asked if

there were cavers who might own as many caves as they’ve discovered. Then,

Ackerman’s at times unorthodox method of exploration likely wrapped up

his spot on the list.

Scratch the surface

Ionoclast Ackerman says of his cave discoveries:

“Generally speaking, this involves finding a sinkhole, excavating it with

a backhoe, and blasting a way in using explosives." These methods

have elicited criticism from caving purists.

“‘With John it’s quicker for him to blast in than find another way in,"

says Blaze Cunningham, secretary of the Minnesota Speleological Survey.

To be fair, he adds, “There is a way of justifying some of it.”’

The article continues, “Fair or not, there is no disputing Ackerman’s

passion for discovering and preserving caves."

The Bluff Country Reader first caught up with Ackerman just 11 months

ago, while touring Spring Valley Caverns. Ackerman and fellow cavers share

an unconditional enthusiasm, respect and urge to preserve these gems lurking

beneath the surface of Fillmore County and surrounding land. As he often

states with reverence, when exploring caves you could be the first person

walking through passages and pristine formations that are hundreds of

thousands, or even millions of years old.

Spring Valley Caverns is part of 500 acres of sinkhole and cave riddled

property north of Spring Valley, land on which he continues to hunt caves

and test theories.

“It’s like gambling. You never know what you’ll find,” said Ackerman.

When asked about the likelihood a sinkhole will lead to a cave, he added,

“I’d say my odds are excellent.”

Cave No. 28

This year Ackerman discovered two more caves at the Spring Valley Caverns

property, No's. 28 and 29. All this came from his recorded attempts to

find caves by excavating “30 or so” sinkholes.

“Most people never find caves when excavating a sinkhole because it could

just be a tiny crack, which could be covered and lost in the process,”

he stated.

Ackerman said he has the experience and “knows the signs,” such as how

rocks react when pulling them out and from which direction to dig. “Then,”

he said, “You try to do it safely. Part of the day is always spent shoring

up (the site).”

Cave No. 28 was found with the aid of what Ackerman calls his modified

“Cave Finder,” a backhoe-type excavator. A crack, which went straight

down, led to a small room and, now, a passage in which Ackerman said he

gains 6 to 10 feet every weekend.

He’s heard a “big echo” around a corner, but the tight passage has prevented

him from putting eyes on it yet. Ackerman will slightly widen the passage

through the use of small explosives. He’s even learned to use them close

to a person’s body as needed in cave rescues.

Cave No. 29

The discovery of Cave No. 29 again put Ackerman’s theories on cave passages

to the test, again successfully. The main entrance to Spring Valley Caverns

sits on a ravine with a building constructed to protect it, while providing

a place for cavers to gather and gear up. Ackerman wondered if the cave

passage might not extend on the other side of the ravine, thinking it

might have been cut through in glaciated times.

In the main passage, using a surveyor-like “precision measuring” tool,

he projected a point on the other side of the ravine, where he felt the

passage at one time might have continued. “I felt it extended many miles

east and west,” he stated.

Measuring with a laser to the top on the hill on the ravine’s opposite

side, Ackerman placed a stake and called a well driller to sink a test

hole.

“We hit a void 50 feet down, right where we thought it would be,” he stated.

Then they drilled another hole 15 feet away, found another void and lowered

a video camera to get a view.

“We encountered a 15 foot wide passage. You could see it continue ahead

into blackness. "We’ll have the well driller create an access shaft,”

said Ackerman, laughing as he added that you know you’ve gone off the

deep end when you regularly call the well driller.

Other caves

He has also has drilled accesses into the 33rd longest U.S. cave, Cold

Water Cave, in Iowa, located just south of the Minnesota border, and at

Goliath’s Cave in Fillmore County. When access to both caves became restricted,

Ackerman purchased land above the caves and drilled his own entrances.

Cold Water Cave is designated a National Natural Landmark. In 2002, Ackerman

bought five acres above the cave system, along with 200 underground rights.

The following year he drilled a 188-foot deep shaft, 30 inches in diameter,

and completed the project in May of 2004.

In the fall of 2004, Ackerman purchased two surface acres and 358 acres

of subsurface rights from Venita Sikkink near Cherry Grove. He said the

Minnesota cavers, who discovered and mapped Goliath's Cave, had their

access taken away when the Cherry Grove Scientific Natural Area (SNA)

was set up through the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources.

Another Reason

This year there were more explorations in Goliath's Cave. Some explorations

involved diving through water filled passages, which are known as sumps.

Ackerman found another good reason to create a cave entrance or further

a cave passage by small, controlled blasts: saving a life, quite possibly

his own.

A harrowing tale of cave diving occurred at Goliath's Cave on Thanksgiving

weekend. Excerpts from Ackerman’s writings follow this article.

Despite the fear of drowning in a cave, Ackerman still can’t wait to explore

the one-third of mile passages he recently discovered in Goliath's. He

also feels another branch of the cave will lead to the Big Spring at Forestville/Mystery

Cave State Park, since a dye trace exited the cave system there.

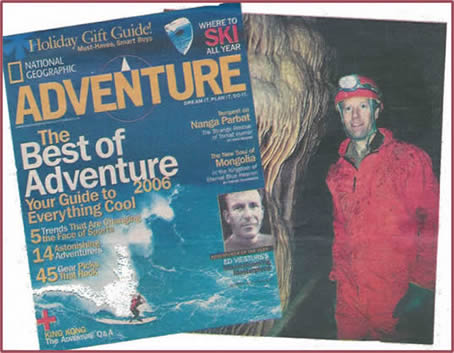

Ackerman laughed to note the photo used in National Geographic Adventure

magazine was done almost as an afterthought. It was taken by National

Geographic photographers at the conclusion of three hours he perched on

a small ledge in Spring Valley Caverns, laden with rope, drill and other

equipment to look like he was going to blast open a passage.

In the end, the magazine editors chose the simple outdoor shot of Ackerman

in his orange caving suit against a yellow field of soybeans ready for

harvest, perhaps showing that spectacular discoveries await most anywhere

for this iconoclast caver.

Ackerman shares firsthand report on cave diving

EDITOR’S NOTES: This is excerpted from a report John Ackerman wrote about cave diving Nov. 26 at Goliath’s Cave in Fillmore County. He first recalled nearly drowning in a cave in 2001 due to a line entanglement, vowing never to dive in caves again. But, Goliath’s Cave proved too tempting.

When I saw the sump (water filled passage) in Goliath’s Cave I was positive

there could be miles of unexplored cave passages beyond, just waiting

for myself. Dave Gerboth, Clay Kraus, Charlie Graling and others to explore.

One need not be a rocket scientist to arrive at the conclusion that this

sump was an award winner. After all, several hundred feet from the sump

lay an old tire lodged between sharp rocks, which had obviously been washed

in from a distant cave on the other side of the sump.

This sump was the ticket, and it had my name written all over it. I must

admit, I was having alluring thoughts of diving it, but thanks to a timely

e-mail from cave diver John Preston, those alluring thoughts were held

in check.

Preston stated in his e-mail that he was an NSS-CDS certified cave diver,

had considerable experience cave diving throughout Florida and Mexico,

and was searching for sumps that needed to be cracked. He would be a perfect

fit for this project, plus he lived only 30 minutes away from Goliath’s

Cave.

On Jan. 15, 2005, Preston and a handful of other experienced divers arrived

at the newly created shaft entrance to Goliath’s Cave, referred to as

“David’s Entrance.” Yes, they may have been expert divers but caving was

not exactly their sport of choice. They were somewhat taken back as they

gawked down the 80-foot entrance shaft after learning that entering the

cave required climbing down the thin, temporary, flexible cable ladders.

Eventually all of them made it back to the sump with the assorted gear

necessary for Preston’s initial probe. I was impressed. Not that they

had made it, but that I could not remember ever seeing so much gear involved

in a sump dive.

With my video camera rolling, Preston slipped into the sump feet first

and disappeared, his thin nylon safety line trailing with him and his

single yellow air tank slowly fading away from our view. After 15 minutes

I became jittery, after all there was no backup plan in the event he did

not reappear.

But eventually he surfaced, ecstatic that his initial probe answered our

questions. Yes, a human could enter the passage and it continued. Now

Preston had a taste of the environment and vowed to refine his gear for

another push.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Other dives were made throughout 2005, leading to November. John Ackerman grew tired of the fantastic secondhand reports.

We listened to accounts of massive pristine formations and incredibly

tall cave routes until the night began to fade to morning. I was growing

weak and tried to fight it. Bit to no avail. I finally limped over to

Preston and whispered in his ear.

“I am going in.”

On November 26, 2005, I found myself hovering over the sump in full gear.

The day had finally arrived. I had gone over this dive a thousand times

in my head. Preston’s sketch map of the water-filled route was actually

imprinted on my brain and I felt that I had prepared, streamlined and

positioned my gear to avoid a line entanglement. I figured I could beat

the odds if I entered the sump ahead of Preston and outpaced the visibility

factor. And so that was the plan.

The first thing to jolt my adrenaline was the fact that although I thought

my weight belt was over weighted, I was actually too buoyant. I had to

actually pull my body down under the water and into the sump. This caused

some turbulence, but I could still see clear water ahead.

Soon I was staring down the steep boulder strewn slope, my body now in

a position to follow it downward. I was instantly shocked when up ahead

I could see that the white safety line was actually buried under four

or five large slabs and rocks. I scoured the ceiling but I found it to

be smooth. I was growing quite apprehensive about continuing but nonetheless

made my way down to the rocks, and as I pulled them off the line I saw

them tumble down the slope with a cloud of silt trailing behind them.

They were quite large and I presumed they could have shifted down the

slope when Preston exited on his previous trip.

A sense of urgency overcame me as I watched my sphere of vision diminish.

After all, I had rationalized early on that clear visibility would make

this a safe dive, at least on the way in. I grasped the line in one hand

and proceeded in my attempt to overtake, the silt. I soon encountered

the blank wall that Preston had described and instinctively turned sharply

to the right.

The passage abruptly changed character and I could now clearly see a long

low sandy passage stretch out in front of me. For a fleeting second it

appeared almost friendly and inviting. That feeling soured instantaneously

as I felt the thin safety line begin to wrap around my air hoses and right

leg, impeding my progress. Of course I knew then that what I had feared

could happen was indeed beginning to engulf my very being.

An urgent sense of panic ensued, but I forced myself to obey my previous

training, which taught me that a calm demeanor is the only ticket out

of a potentially life threatening line entanglement – or any dire situation

that may occur under water. I was all too aware that my life had been

saved back in 2001 because I had indeed remained calm. No matter what,

I wanted out and I wanted out now.

As I was moving forward I could see the inky black cloud catch up to me

and I desperately did not want to deal with this situation in a blackout

state. As soon as that happens problems seem to intensify one hundred

fold. I could feel the line slide by my shoulder assembly and around my

leg as I slid ahead, gradually securing its grip on me. I knew that soon

I would be stopped dead cold in my tracks.

All of the sudden something caught my attention and I instinctively looked

up. What an incredible lucky break. I could see and hear pounding water

about 20 feet up. My only thought was for me to pull myself and the line

up to the surface, where I could stick my nose into that life-saving air

space. From there I could untangle or cut the line at will.

When I reached the surface my instantaneous thought was that I had again

cheated death and won. I threw my mask back onto my head, twisted my air

valve off, unraveled the line, worked my way onto solid ground and promptly

thanked the Cave Gods that I had survived. A few minutes later John popped

up unscathed and in good spirits.

Over the roar of the rapids I declared that my trip in was anything but

a cakewalk. He nonchalantly responded by stating that he had seen the

line entanglement and had pulled it partially away from my leg. I wondered

if this was entirely truthful or if he was attempting to calm me down,

knowing full well that the most dangerous portion of the trip would be

the silt out exit.

EDITOR’S NOTE: After exploring and making great discoveries, it was time for the dangerous trip out.

My light had pierced over one-third mile of pristine unknown cave passages

and I felt overwhelmingly dumbfounded.

As we accelerated closer and closer to our main cache, I felt my security

level begin to diminish. I was leaving a place of solitude and trading

it for a place I knew as tumultuous, raw and uncivilized.

Preston and I were acutely aware that our deadline was near at hand as

we broke out the water and “Power bars.”

Sorting, assembling and gearing up seemed to take forever, but I suppose

if Preston didn’t have to stop every 15 seconds to answer one of my “what

if” questions, the procedure could have been done in no time at all.

I had my line-cutter pre-positioned in the sheath along my left side just

like a cowboy has his trusty gun in the holster. Now fully geared, I climbed

down the incline to the top of the water, slid in, pressed my knees against

the passage wall and sat there, staring at the thin white safety line.

Preston shouted through the labyrinth of sounds, pointed to the line,

and reminded me “the line is your friend.”

“Yeah, right,” I mumbled, “just like the wolf is Little Red Riding Hood’s

friend.”

“And don’t let go of it for any reason,” he pleaded. “Slide it through

your left hand as you inch forward. It will take you all the way out.”

“Easier said than done,” I responded. “What if it works its way into a

crack around the corner?” I asked. “Do exactly what I said before…keep

your body away from it and hold it at arms length. Your body will feel

its way through the largest portion of the passage and you will have no

trouble.” Preston shouted back.

“OK, great, now I know where I went wrong before, I let my brain get involved,”

I quipped.

“Exactly,” Preston said, “don’t even use your diving light. It is worthless

down there anyway. Just close your eyes, concentrate on the line and move

slowly forward.”

“No way” I replied. “I want to use the light anyway.” “OK,” Preston said,

“Then hold it two inches away from the line and follow it out.”

EDITOR’S NOTES: John Ackerman did get hung up on the way out.

With that I shoved the regulator into my mouth, took 2 breaths and slipped

under the surface for what I hoped would not be the ride of my life. I

successfully pulled myself all the way to the bottom while allowing the

line to slide through my hand, just like the plan called for. “Good” I

thought. “Just like a pro.” When I reached the bottom I held the light

out against the blank wall to feel for the opening and surprisingly my

light highlighted a sharp projection that protruded outwards. “I certainly

did not see that feature on the way in” I thought. I felt my feet slide

under it slightly and took that as a clue that I should lay on my belly

and slide under the projection. As I slid under it I knew I was now laying

on the sandy flat passage and felt that so far this had been a reasonably

good start. That was until I was stopped cold.

At first I thought I was tangled in that “friendly” line, but after groping

around I discovered that my tank had come loose from the attachments and

was floating behind and above me, against the wall I had just left behind.

This was just the type of nightmare I feared would happen in this house

of horrors.

“Should I grab the tank, pull it down and attempt to leave this inky black

abyss while dragging it out with my right hand?” I asked myself. “No,

I am going all the way back up,” I decided.

As I resurfaced I told Preston I had come back for the party, but I could

tell he was not amused, and quickly re-adjusted my harness setup. “Boy,”

I thought as I slipped back into the icy 48-degree water, “I was lucky

to get to do this again.”

Within minutes I found myself back down in the flat sandy passage, moving

gracefully along. Things were finally going my way. I held my light 2

to 3 inches away from the line and let it slide by as I moved ahead.

Before long I met up with the final solid wall and gracefully traveled

to the left, along with the line. I kept my body well into the passage,

away from the line, and as I made my way up the boulder slope my brain

kicked in and actually thought that this was kind of neat.

Life was good, but as I was right in the middle of relishing my accomplishment

I saw an annoying bright white light from above. “No wonder I was having

so much fun” I thought “I must have drowned down there in this miserable

death trap.”

The light was getting brighter and brighter and I could feel myself floating

higher and higher. “Geeze,” I thought, I hope I get to at least experience

some of those flashbacks that I heard were so great before I am totally

gone.”

Then, without warning I was jolted back into reality. The first thing

I saw was an unshaven Clay Kraus staring down at me with his million-candlepower

headlamp. Oh, that’s right, earlier I had asked him to shine his light

into the sump for my return, you know, kind of like leaving the front

door light on.

After a few moments my cells collected back together, and before I could

relay the discovery news to my comrades, I reminded them that it was good

to be alive. Soon thereafter Preston surfaced safely with his massive

gear cluster, but stated that when he had arrived at the bottom of the

first drop his air supply had ceased. He said he calmly reached around,

located his main supply knob and found it to be totally closed. The explanation?

The exposed knob had rolled along the wall on the way down, gradually

spinning it totally closed. I wondered what my outcome in a situation

like this would have been.

During our immediate celebratory debriefing Dave had a hundred questions,

but started off asking John Preston where all the other divers were and

why they did not accompany us today. Without hesitating Preston responded,

“”Every last diver refused to go through that sump.”

Gulp.

When “David’s Entrance” was installed into Goliath’s Cave last year I

made the statement that there were major unknown sections of this cave

system just waiting to be discovered. So far, with hard work and diligence,

we have had three pre-eminent break-throughs, which I estimate have expanded

the cave to over three miles.

I would like to take this opportunity to sincerely thank the entire caving

community for all their support – and would especially like to thank John

Preston for bringing us this incredible find.

EDITOR’S NOTE: John Ackerman later said, “Based on calculations, we think we can create a dry route (to the new section beyond the sump). We think it’s only 15 feet through a rock wall. We’ll do the calculations and then put a 30 inch wide horizontal passage (through the wall) into the new section.