The

Post-Bulletin, Rochester MN

8/21/2010

Could pipeline wreak havoc on cave?

By

Laura Horihan

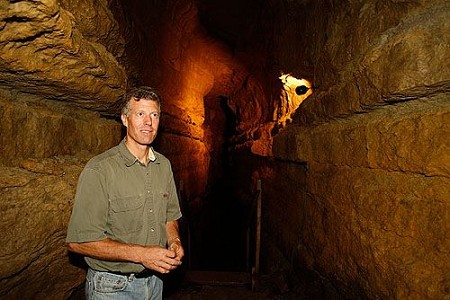

SPRING VALLEY — On a recent hot July day,

spelunker John Ackerman of Lakeville unlocked the door that leads to Spring

Valley Caverns, the state's largest privately owned cave and the largest

cave on his farm north of Spring Valley.

Inside the stone structure, backpacks littered the floor, left behind by children exploring the cave with guides from Quarry Hill Nature Center in Rochester.

They're the reason Ackerman worries about a nearby BP pipeline.

Ackerman fears that if the pipeline would break, fumes could kill people exploring the cave and the hazardous material would wreak havoc on the cave's fragile eco-system, as well as on the creek that flows into Bear Creek and eventually the Root River.

The cave entrance, located in woods near Fillmore County Road 1, was discovered in 1966 by a young farmer who had recently purchased the property.

An early commercialization effort never panned out. When Ackerman purchased the farm in 1989, he knew there was a nearby pipeline, but he had no idea that the cave would run five miles underneath it.

Back then only half a mile of passageways were accessible, but with the help of explosives about five miles of the cave is now open.

Off and on since 1994, Ackerman has corresponded with officials with Amoco, which merged with BP in 1998, in hopes that the company will send workers out to inspect a section of pipeline that lies directly under a flowing stream that dumps into his cave.

"One would hope they would have just a hint of curiosity regarding a potential catastrophe just a few miles from their terminal," Ackerman said.

Ackerman believes the pipeline has never been physically inspected since it was built.

But BP officials say they last inspected the pipeline in July 2009 and found no problems.

"Operating the pipeline safely is top priority for us," BP spokesman Ronald Rybarczyk said. "Our intention is to prevent issues before they arise."

The Minnesota Office of Pipeline Safety records show that office completed inspections in 11 of the past 15 years of the pipeline.

Ideally, Ackerman would like the company to move the pipeline, but he's only asking that they install a shut-off valve in the cave's vicinity.

"Everyone knows we need oil and gasoline, but when the pipeline was laid in the 1940s, people didn't know anything about karst features," Ackerman said, referring to the geography of the land characterized by numerous caves, sinkholes, fissures, and underground streams.

|

John Ackerman owns Spring Valley Caverns in Fillmore County. Ackerman is worried that if an active BP pipeline on his property were to break, it could contaminate water, destroy the cave network or cost explorers their lives. "One would hope they would have just

a hint of curiosity regarding a potential catastrophe just a few

miles from their terminal," Ackerman said. |

The pipeline was commissioned in 1948 and transports finished products like gasoline or diesel fuel from Dubuque, Iowa, to a New Star terminal in Roseville.

The section that concerns Ackerman runs directly under a blind valley, where flowing surface water abruptly drops into the ground, travels underground and reemerges at the surface.

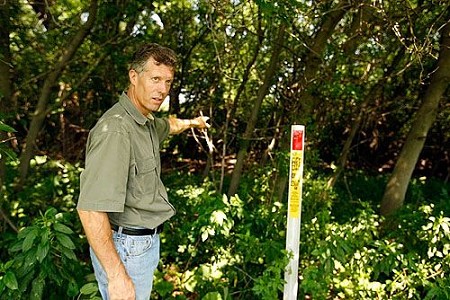

Hundreds of feet away from the cave's entrance there's a grove of trees with a creek meandering through it.

"Sometimes the water rushes and other times it's merely a trickle," Ackerman said.

Two markers, one on either side of the grove, indicate the pipeline's path.

Ackerman believes the flowing water could be slowly eroding it.

"The pipeline isn't buried very deep," Ackerman said. "A

farmer nicked it with his plow before I bought the land."

University

of Minnesota geology professor Calvin Alexander, with the help of his

students, did two dye traces in 2006 and discovered that the water flows

through the cave and re-emerges about 2 miles away, near Fillmore County

Road 1. The water from the cave eventually flows into Bear Creek, which

dumps into the Root River.

A nearby cave owned by John Ackerman owns Spring Valley Caverns, a 5.5-mile long cave system in Fillmore County and the largest privately owned cave in Minnesota. Ackerman is concerned about a BP pipeline on his property that, if broken, could contaminate water, destroy the fragile cave network or cost cavers their lives. Ackerman says he has contacted BP several times, to no avail.

"It'll happen when no one is watching ... when (John) Ackerman's got a bunch of kids in that cave or when I've got some of my students in there doing research," -Calvin Alexander |

"Our primary concern is for nearby neighbors, our workers and safe and reliable operation of the pipeline," Rybarczyk said. "We've sent a letter to him expressing our concern over excavation near the pipeline." -Ronald Rybarczyk |

SPRING VALLEY — On top of the usual dangers of cave exploring, spelunker John Ackerman worries that a BP pipeline running through Spring Valley Caverns will one day break, endangering fellow cavers and harming the fragile formations developed over thousands of years.

In 1989, Ackerman began developing the Minnesota Karst Preserve in a collection of privately owned caves in Fillmore County, to study and preserve them.

His property in southeastern Minnesota and northern Iowa encompasses 39 caves.

Over the past 16 years he's been corresponding with BP, requesting that they inspect a section of pipeline that runs through one of his caves near Spring Valley.

Ackerman believes company employees have never come out to his property to inspect the pipeline.

But BP spokesman Ronald Rybarczyk said the pipeline that runs from Dubuque, Iowa, to Roseville was inspected as recently as July 2009 and that no anomalies were detected.

Kristine Chapin, a spokeswoman for the Minnesota Office of Pipeline Safety, said electronic records show that the office has completed inspections in 11 of the the past 15 years.

"His fears that it has not been inspected are not valid," Chapin said.

She said it's likely that the section he's concerned about was inspected with the help of a "smart pig," a device that takes readings of wall thickness and detects minor pitting, cracking or dents in the pipe.

Rybarczyk said he isn't sure if BP employees ever have dug down to the pipeline to inspect its condition but said that likely wouldn't happen unless a "smart pig" found an anomaly.

"Operating the pipeline safely is top priority for us," said BP spokesman Ronald Rybarczyk said. "Our intention is to prevent issues before they arise."

From a control center in Tulsa, Okla., workers can monitor the pressure in the pipeline, Rybarczyk said.

Ackerman believes thousands of gallons of fuel would spill into the caves before BP recognized a problem and shut down the line.

Rybarczyk said BP also does periodic visual inspections of the pipeline with fly-overs or foot patrols.

Ackerman is most concerned about a section of pipeline that runs directly under a valley, but it's currently covered by several large trees.

He said BP has contacted him about cutting them down, but he refuses to let them because he believes "the tree's roots are probably keeping the ground from eroding and holding the pipeline up."

The complaints go two ways. Ackerman has been doing some excavation near a cave he recently discovered, and BP believes he's been working too close to the pipeline.

According to Rybarczyk, Ackerman called Gopher One Call in April to have the pipeline marked.

After the lines were marked, Ackerman had 14 days to complete the work, but during a flyover on July 23, a pilot reported seeing Ackerman's backhoe within 2 feet of the pipeline and a pile of dirt directly over the line.

Ackerman said he's stayed at least 25 feet away from the pipeline while doing the work.

"Our primary concern is for nearby neighbors, our workers and safe and reliable operation of the pipeline," Rybarczyk said. "We've sent a letter to him expressing our concern over excavation near the pipeline."

He's not sure if a formal complaint has been filed with the Minnesota Office of Pipeline Safety, but he said that if the incident occurs again, BP will contact the attorney general's office.

Even if Ackerman allows BP to remove the trees in the valley, University of Minnesota geology professor Calvin Alexander doubts someone flying overhead would detect a spill.

Alexander has been doing geological studies in caves since the 1960s.

"Unlike other spills, the fuel will not sit on the surface," Alexander said. "Instead, it will follow the water right down into the cave. They won't be able to see it overhead."

He said water from the cave re-emerges about 2 miles away and that BP wouldn't look for their petroleum products there.

"Sooner or later someone will figure it out, but it will spill a lot of fuel in the process," Alexander said. "These things happen all the time, but with karst it can go places you're not expecting."

Alexander has also sent letters to BP officials regarding his concerns, but he's never received a reply.

David Morrison, an emergency response specialist with the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency, agrees that a spill could cause significant damage to the environment.

In an e-mail to the Post-Bulletin, he wrote that the pollution control agency is concerned about the proximity of the pipeline to the underground cave network as well as other environmentally sensitive areas in Fillmore County.

"A release from a pipeline in these areas could create a serious threat to the environment as well to public health and safety," Morrison said. "Aside from the damage to the caves and cave biota itself, nearby wells would be at risk, streams and sensitive wetlands would be at risk, and the upper aquifer would be affected."

Sometime between 1994 and 1996, pollution control agency staff met with Ackerman at a rest stop in Cannon Falls.

At the time, Ackerman and the agency showed interest in getting more information about the condition of the pipeline.

Morrison said they agreed to research information about the caves, how the water drains into them and what can be done regarding emergency response.

Morrison said Ackerman's concerns were brought to the attention of the Office of Pipeline Safety, Amoco (which owned the pipeline at the time) and the Spring Valley Fire Department.

Minnesota law requires pipelines to plan and prepare for responding to spills, and the company is required to identify environmentally sensitive areas and come up with a plan to protect them.

In 2000, BP reported an oil spill that occurred in 1997 at its terminal east of Spring Valley.

At the time, the company was ordered to clean up contamination from several smaller spills that took place at the terminal over a 40-year period.

According to a Post-Bulletin story from Aug. 25, 2000, 40 truckloads of dirt each day for 11 days were removed from the site.

A sample from a nearby well tested positive for a small amount of chemicals that could have come from the terminal.

Spring Valley Fire Chief Troy Lange said his firefighters have been trained to deal with emergencies at the terminal. He said they know who to contact locally if the line needs to be shut off.

However, he said, the department has never been invited to Ackerman's caves, and they've never been trained on how to handle an emergency there.

"We do have some rescue gear with ropes and harnesses, but we prefer that trained people do that work," Lange said.

The Minnesota Department of Natural Resources has set up a rescue team for cave emergencies, Lange said.

If a disaster does happen, Alexander fears it will happen at the most inopportune time.

"Murphy's Law is that anything that can go wrong will go wrong at the worse possible time," Alexander said.

He believes Murphy was an optimist.

"It'll happen when no one is watching ... when Ackerman's got a bunch of kids in that cave or when I've got some of my students in there doing research," Alexander said.

A nearby cave owned by Ackerman was recently the site of an important archaeological find. The skull of a saber-tooth cat and the antler of a prehistoric stag moose were found in Tyson Spring Cave.

"If there was a pipeline disaster, God knows we wouldn't find any bones in the mess left over," Ackerman said.